Slavery and Freedom

Waterford's African-American Experience

Excerpted from, "Share with Us, Waterford, Virginia's African-American Experience", a booklet written by Bronwen and John Souders for the Waterford Foundation. .

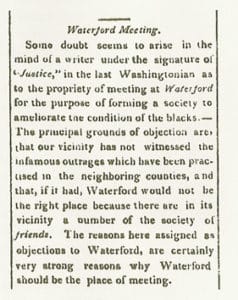

In the heart of the village, within a few doors of the Corner Store [40183 Main Street], there are several reminders of both the best and the worst of Waterford's African-American experience. The town is notable for the relatively large numbers of free blacks who made their homes in the village in the days of slavery. They were drawn by the opportunity to be found in a thriving farm village – and by the tolerance and encouragement of the local Quakers. In 1818 the Quakers and other white residents even proposed to form a "Negro Protection Society" to curb abuses more common elsewhere in Virginia (see clipping).

In this welcoming environment, free blacks were able to buy property. Nero Lawson purchased a lot on Water Street in 1818 and built a house. Lawson evidently brought with him to the village a young orphan, Nathan M1nor (1788-1873), whom he had taken on as an apprentice farmer in 1795. Nathan managed to learn a good deal more than farming. His purchase of writing paper in Waterford in 1816 indicates that he was 11terate, even though Virginia at the time strongly discouraged the education of blacks. He went on to own two houses of his own along Water Street, In the 1850s Nathan's daughter Sarah was the only black woman merchant on Loudoun County's tax rolls.

But life for African-Americans in pre-Civil War Waterford could be much harsher, Many neighboring farms employed slave labor, and even a few townspeople owned or hired slaves. More than one was bought and sold at public auction on Main Street in front of the taverns that, in the first half of the 19th century, flourished along Arch House row [40158-40174 Main].

The Weavers Cottage (c.1820, 40188 Water Street)

In 1854 African American William Robinson, 24, freeborn son of a free woman, Nancy Robinson (c.1814-1884), bought this log and fieldstone house. It had belonged to a German-born weaver. The Robinson family made it their home for more than 100 years. William's younger brother Noble and his wife, the former Emma Gather, raised a family of eight children here (and took in others, including Noble's brother Robert). Noble was a jack-of-all-trades, but is perhaps best remembered for his small shop, which stood to the left of the house, where he sold ice cream in the summer and oysters in the winter. Along Water Street to the right of the Weaver's Cottage once stood two more houses. They were built by free black owners early in the 19th century. By the end of the century, though, they had become unsafe. One, owned by Sarah Minor, was demolished in 1895 on order of Waterford's Town Council.

Pink House (c.1816-1824, 40174 Main Street

This three-story brick building was known originally as Klein's Tavern, after its first owner, Lewis Klein (1783-1837 Centra1y located, it was for many years an important social and commercial hub in the village. Klein, who owned slaves himself, was undoubtedly pleased to offer his establishment for the sale in 1830 of a local slave trader's holdings. (See ad on facing page.)

Arch House Row (40158-40176 Main Street).

This group of buildings has a complex and intertwined history, as the interior partitions between them have been rearranged repeatedly over the years. From around 1810 the middle third of the row served as a tavern under a long succession of owners. Here, in 1815, Loudoun County's first bank was organized, and in 1836 Waterford gathered at the tavern to elect its first town council. But here, too, "before the door" slaves were bought and sold as early as 1819.

Aunt Laura" Page

The stone structure [no longer standing] was one of the final homes of Laura Page, a well-liked woman who had been born into slavery about 1845 Well into the twentieth century whites often referred to respected members of the African-American community by the informal honorific "aunt" or "uncle" – although most blacks preferred, and used, Mr. or Mrs.

As a slave, young Laura was one of several owned by William Cassady on his large farm about a mile east of the village. After the Civil War and emancipation, she worked on the neighboring Smith form as a house servant. She evidently was a family favorite, for one of George Smith's daughters left her $100 in her 1888 will – with the unusual stipulation that her husband was to have no say in how she spent the money.

Laura Page

Laura had undoubtedly met her husband. Andrew Page, on the Smith farm, where he too, was employed after the war. It is not clear why Eugenla Smith thought it wise to keep her bequest out of Andrew s hands. He appears to have been a reliable husband and worker. He and Laura eventually returned to the Cassady farm, where, among other duties, Andrew drove the carriages outfitted in a handsome livery.

The Pages had 12 children, the first two at least born before their marriage was formalized in the 1870s-Virginia rarely recognized unions between slaves. After Andrew s death – he was some twenty years older than she – Laura moved into Waterford. She lived with a grandson and worked as a laundress.

Laura Page House (site)

After the Civil War, Waterford's African Americans enjoyed better times. And, ironically, in the early years of the 20th century, much of Arch House Row passed into black ownership. The brick building at the left end of the row belonged to the Coates family into the 1990s. One woman who grew up in another of the buildings laughs about the embarrassment of her prim and proper mother about living in a "former tavern".

Across Main Street (40155 and 40157 Main Street)

Opposite Arch House Row there is another, smaller row of buildings. They are the remnants of a structures that formerly stretched along the southwest side of Main Street. (See photo) The stone building at the right end of the row was demolished in the 1930s. One of its last residents was Fred Jackson, an African American who worked as a chauffeur to Virginia Governor Westmoreland Davis, of nearby Morven Park, around 1920.

The house at the far left of the row was the home of another African American, Theodore Mallory, until it was destroyed in February 1965 in a fire that began in the house to its right. The blaze reportedly began with a misguided attempt by the resident to keep a hive of bees in the attic from freezing. Over the years many black families made their homes in this row of buildings. During the first half of the twentieth century, street scenes like that below of young African-American children at play were common.

© 2002 Waterford Foundation, Inc.

xwx